Inside the making of Wes Anderson’s meticulous, miniature worlds

London’s Design Museum unpacks 700 items charting the director’s movie-making.

The Good Life remixed - A weekly newsletter with a fresh look at the better things in life.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In spring 2009, I visited Three Mills in East London. Within this complex of canal-side film studios, a puppet department of 23 craftspeople were bent over work benches, finessing the finicky detail on 500 mammalian figures in six different scales. At that point they – and dozens more colleagues based at the Manchester atelier of master puppeteers Mackinnon & Saunders – were two years into the project, and they weren’t done yet. It’s fair to say that everyone was very tired.

This was the set of Fantastic Mr Fox, the sixth film by the American director Wes Anderson. Even accounting for the fact that this was the filmmaker’s first adventure in stop-motion animation, production on the 93-minute film based on Roald Dahl’s book had involved unfathomably Herculean labour.

For banjo-playing Petey, modelled on Jarvis Cocker, the angular singer’s signature real-life moves required the team to create bespoke ball-socket joints, using Swiss watch bolts. Anderson’s specified pallor for Farmer Bean (voiced by Sir Michael Gambon) meant 15 coats of paint. Rat – king of Farmer Bean’s cider cellar and voiced by Willem Dafoe as if he was a New Orleans gangster – wore a tiny striped, woollen jumper. That had to be knitted. But only after the team had whittled itsy-bitsy knitting needles.

At this point, six months out from the film’s release, there had been 15 different puppet versions of Mr Fox (George Clooney), ageing from a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed young cub to the wily Vulpes vulpe who, by the film’s end, is a battered survivor of his battles with Dahl’s demon farmers. One thing remained standard, though: his tight suit in “fabric from one of my suits”, the dandy-ish Anderson, who also wore his suits snug, told me. “Mr Fox’s suit is made of orange-ish, brown-ish corduroy. It looks like the colour of a leaf in autumn, and we wanted the whole movie to look like the fall.'

Sixteen years on that pernickety, Purposefully Wes Anderson detail – there-not-there in all his films, the microscopic detail making for a phantasmagorical whole – is on loving display at London’s Design Museum.

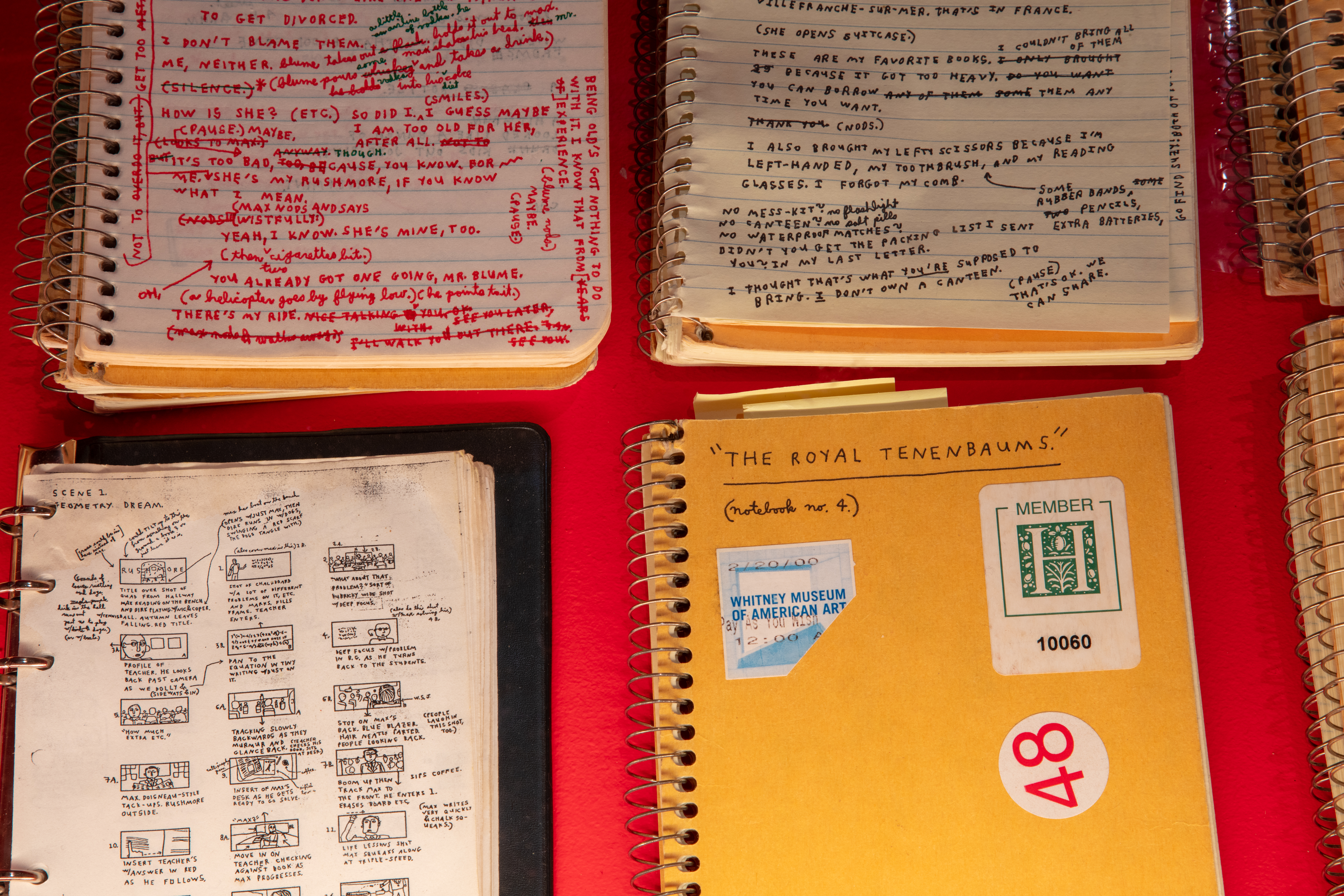

Wes Anderson: The Archives is a 700-item exhibition celebrating both the big-screen wonderland and the nuts’n’bolts hinterland of his filmography, from Bottle Rocket (1996) to this year’s The Phoenician Scheme, his 12th feature. It’s drawn from the director’s clearly bottomless personal hoard of papers, annotated scripts, onset Polaroids, production sketches, props, costumes, animatronic fox parts and six different kinds of fake canine fur for his second stop-motion fantasia, Isle of Dogs (2018), also made at Three Mills.

The detail flex of the Anglophile and Francophile Texan auteur is, naturellement, astonishing, from the very first kernel of inspo. The earliest script jottings – whether “Oceanographic Movie (that’s 2004’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou) or “India Movie” (2007’s The Darjeeling Limited) – all begin on Narrow Ruled Eye-Ease Paper in National Brand Single Subject Notebooks. Anderson’s hand-drawn storyboards are works of art in themselves.

The contributions of his carefully assembled repertory company of repeat actors (Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Luke Wilson) are valourised in photographs from the New York set of The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) and the Spanish set of Asteroid City (2023). Those can be either snappy snaps – or, in the case of the images of Scarlett Johansson filming Asteroid City, they’re shot in the style of the Magnum photographers who documented production of The Misfits (1961), the final film of both Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable. So, that’s behind-the-scenes on behind-the-scenes. An in-reference for the in-crowd.

Hulking at the heart of the exhibition is the titular building from The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), incarnated in a three-metre wide, candy-pink model, the better to shoot authentic-looking exteriors. That’s Anderson: always simultaneously thinking big and thinking small.

And deeper, further he goes. The bespoke collaborations – Louis Vuitton for the luggage on The Darjeeling Limited, Adidas for the submariners’ footwear in The Life Aquatic – are no-expense-spared and no-detail-missed. The world-building is both total and witty: in the (non-animated) The French Dispatch (2021), Cocker is the voice actor behind Tip-Top, a beloved chansonnier. That meant creating an album by Tip-Top, Chansons d'Ennui (Songs of Boredom), the beautifully designed, 12-inch sleeve of which is on display.

Much like Anderson’s films have become since The Grand Budapest Hotel, his biggest box-office success, it is, then, a lot.

But whereas in the films it increasingly feels like plot and drama have been sacrificed on the altar of whimsy, antic and mannered Wes-speak, and look-ma-no-hands lavishness, in the exhibition context – in a Design Museum context – Anderson’s unique vision makes considerably more sense. We can pore over the details. We can let the experience sink in. We can luxuriate in the handcrafted precision of canoe (2012’s 1960s-set Moonrise Kingdom) and caboose (the retro-rail fetishisation in The Darjeeling Limited). We can raise an amused, “but of course” eyebrow when we learn that a version of Marc Jacobs’ Darjeeling luggage was included in Louis Vuitton’s autumn 2025 collection “under Pharrell Williams’ guidance”.

Here, under glass and exhibition spotlight, accompanied by audio guides, film clips and the drifting sounds of his soundtracks (equally painstakingly compiled), you can lose yourself in the wonderful world of Wes. With its constituent parts lovingly broken down it is, paradoxically, a more immersive, more rewarding experience than his latter cinematic excursions. Here, in the stillness of the gallery, Anderson’s monomaniacal attention to detail makes glorious, vivid, hugely impressive sense.

Back in 2009, I also talked to Felicity “Liccy” Dahl, the author’s widow and guardian of his estate. She’d often visited the Three Mills set of Fantastic Mr Fox and had seen first-hand just how far the filmmaker was pushing his puppeteers and production designers. “Wes is a hard taskmaster,” she acknowledged. “When you work with somebody who’s really, really good, they generally do drive you mad. But it’s worth it. Never work for mediocrity!”

Wes Anderson, The Archives is open at The Design Museum now.

The Good Life remixed - A weekly newsletter with a fresh look at the better things in life.

Craig McLean is Consultant Editor at The Face. He has written for a wide variety of publications.